Many people who are not into caving and don’t know a thing about speleology have heard this cave-related word pair – stalactites and stalagmites. They know that they are made of rock, and one of them hangs down from the ceiling and the other rises from the ground. Which is which? No idea? We’ll tell you.

This article sheds light on some of the most interesting formations accessible in a cave – stalactites and stalagmites.

Which is which?

To get that out of the way, use a memory technique. “Stalactite” contains the letter “C” for “ceiling”, “stalagmite” contains the letter “G” for “ground.” There you go, never to be forgotten again.

Different materials of stalactites and stalagmites

Contrary to popular belief, stalactites and stalagmites are not always composed of “rock”. For example, the most common stalactite that many of us have seen are ice stalactites – icicles. Ice stalactites not only form on your roof but also in many caves, either at a specific time of the year or in colder caves, permanently. In addition to ice stalactites, there are also ice stalagmites, which form on the ground.

There are also lava stalactites and stalagmites which form in natural caves called lava tubes. Lava stalagmites are much less frequent compared to stalactites as the lava dripping from the ceiling is often carried away by the moving lava masses on the floor, and there is no chance for a stable formation of stalagmites.

For a caver, however, the main type of material for stalactites and stalagmites is limestone. Limestone stalactites and stalagmites comprise some of the most common speleothems (cave formations). Limestone stalactites and stalagmites are mineral deposits that are continually (albeit very slowly) growing. The average growth rate for a limestone stalactite is 0.0051-0.12 inches (0.13-3 mm) a year.

The formation of limestone stalactites and stalagmites

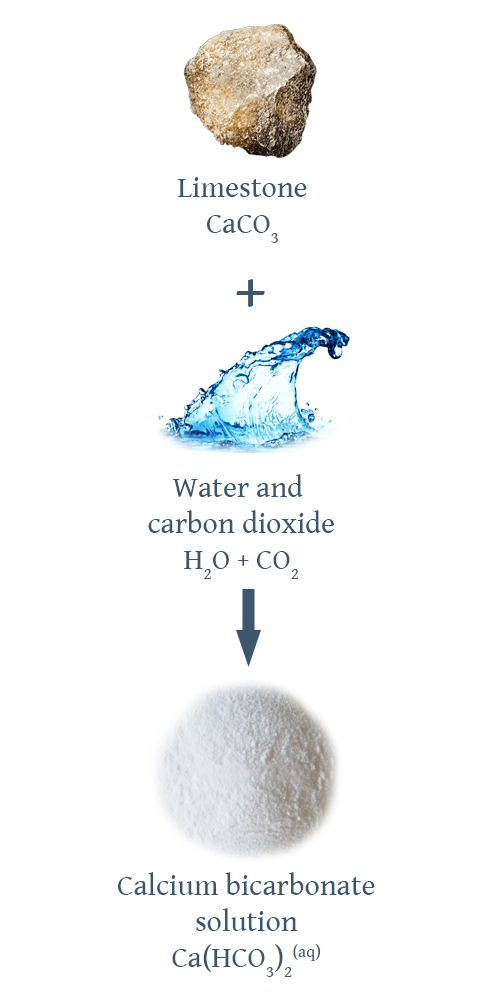

This process is quite simple and illustrated in the following figure. When rainwater seeps through the rock, it picks up carbon dioxide from soil organisms along the way. This CO2-rich water then reacts with limestone, and a solution called calcium bicarbonate is formed. This solution then travels downward until it reaches the air of the cave.

Once this calcium bicarbonate solution reacts with air (that is, once it has traveled through the already existing stalactite and reaches the end of it), the reverse reaction happens, and calcium bicarbonate is turned back into limestone (CaCO3). This limestone is now deposited at the end of the stalactite, thus making it larger. Some of the solution at the end of the stalactite may drip to the ground before it turns into limestone and forms limestone deposits on the ground, and this is how stalagmites are born.

Whether the calcium bicarbonate solution is turned into limestone at the tip of a stalactite or whether it reaches the ground and forms a stalagmite, is dependent on how quick the drip rate is as CO2 needs to degas from the solution before limestone is formed.

In addition to or instead of calcium carbonate, many other minerals may exist in this solution and they all may result in different formations.

Types of stalactites and stalagmites

Stalactites always begin as formations known as “soda straws” (the official term is “tubular stalactite”). First, a single drop of deposit, usually on the cave roof, leaves a small “ring”. These rings accumulate over time and form hollow tubes. Calcium bicarbonate solution drips through the tube and keeps creating new rings, thus enlengthening the tube. Some soda straws can grow very long but are always extremely fragile. Long soda straws are very rarely seen in any public caves at arm’s length since even a slight touch can crush the formation.

If any debris happens to block the inner duct of a soda straw, more water starts to travel outside the tube, and a regular, thicker, stalactite starts beginning to form.

In addition to soda straws, another fragile type of stalactite includes helictites. These form sideways as if gravity doesn’t have any effect on them. In reality, capillary forces act on the droplets of solution, which can force them sideways as gravity has little effect on these droplets due to water’s natural surface tension and adhesive forces between the solution and already formed deposits. Several forms of helictites exist and have been named by cavers and speleologists – these forms include butterflies, worms, ribbons, saws, rods, hands, etc.

Given enough time, a stalactite and stalagmite may meet, forming a single stalactgmite (see what I did there?). These formations are called “columns,” or “stalagnates”. Columns sometimes form simply by stalactite reaching the floor without meeting a stalagmite.

There are also chandeliers, complex clusters of stalactites, requiring precise conditions to form.

In addition to stalactites and stalagmites, collectively known as “dripstone”, there are many other speleothems, such as flowstone, cave crystals, speleogens and other formations which may form, depending on the type of the cave, its mineral content, the availability of water, and many other conditions.

I always remembered that stalactites tike a pair of tights hand down lol. Your way also helps with spelling too.